Did you grow up hearing your family stories? Did you sit around the kitchen table or in the yard in a circle of lawn chairs with grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins hearing a family name?

I’m not talking about family that lived in another state that might be getting a second house or a second wife, or the really good stuff when they’d whisper to each other things like “I hear she’s a … city girl.” I’m talking about real stories of the lives of your grandparents or relatives in another country?

That’s exactly how I grew up. Both sides of my family had reunions at one time. I remember running around the yard or down the street with a gaggle of cousins regularly. Because we moved to Oklahoma in 1984, those cousins had remained just that in my mind – a happy gaggle. Only recently have I straightened out which Duncans and Suttons belonged to whom.

With that in mind, the following is an actual conversation I had with my mother.

“So that one belongs to Uncle Pat?”

“Yes. His name was actually Don.”

“OK…So Uncle Pat/Don and Aunt Tic”

“Yes. But her name’s not really Tic. Her name is Juanita.”

“O…K… Who do those twins belong to?”

“They’re not twins.”

“Yes, there are! Look at them. They look just alike!”

“They’re not even siblings. We all just look alike because our great-grandparents were cousins.”

“… Um, ok.”

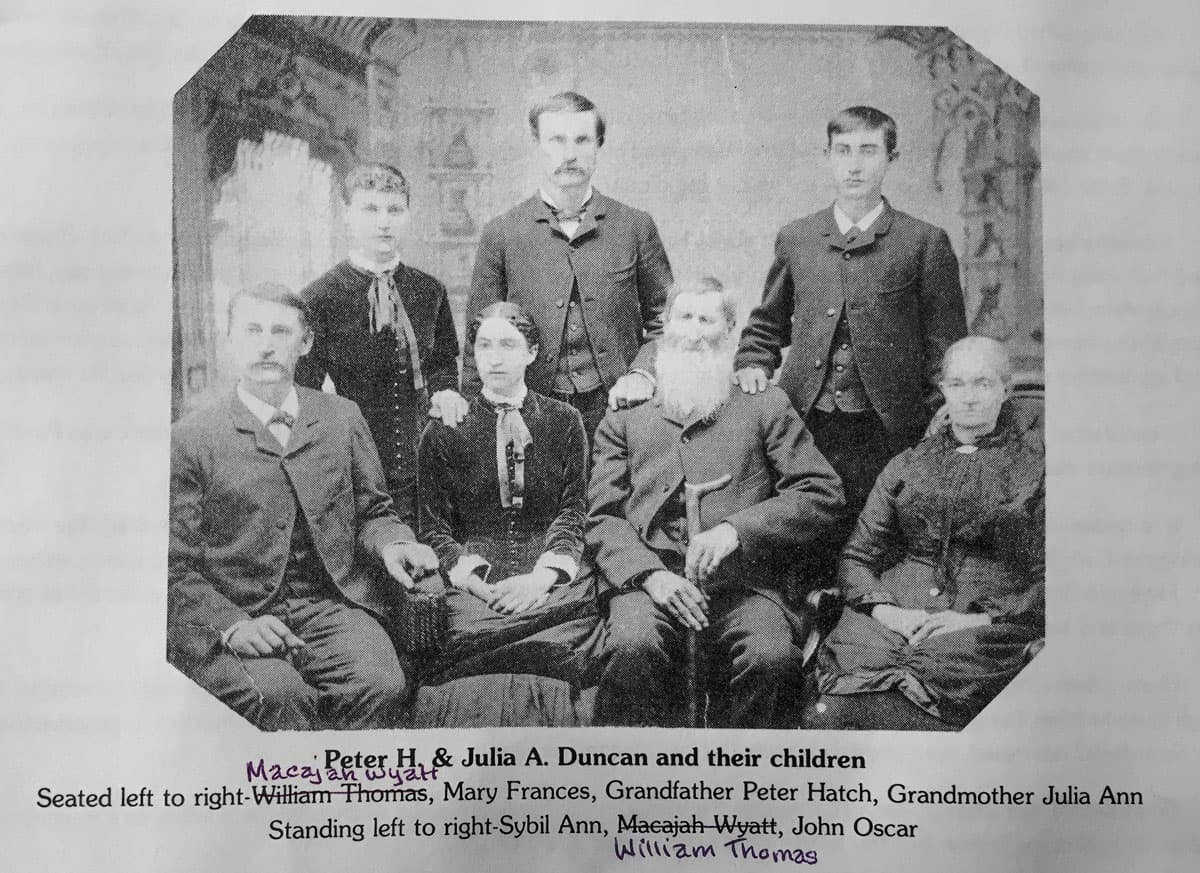

That little piece of information, although alarming, came as no surprise. When both sides of your family have been in one county since statehood (this was Missouri, so around 1821), you’re bound to run out of non-related marital options. Mom’s Duncans and Dad’s Houxes could have 12 to 14 children, and THOSE children could have 12 to 14 children, so my families accidentally founded several towns just by raising families on their lands.

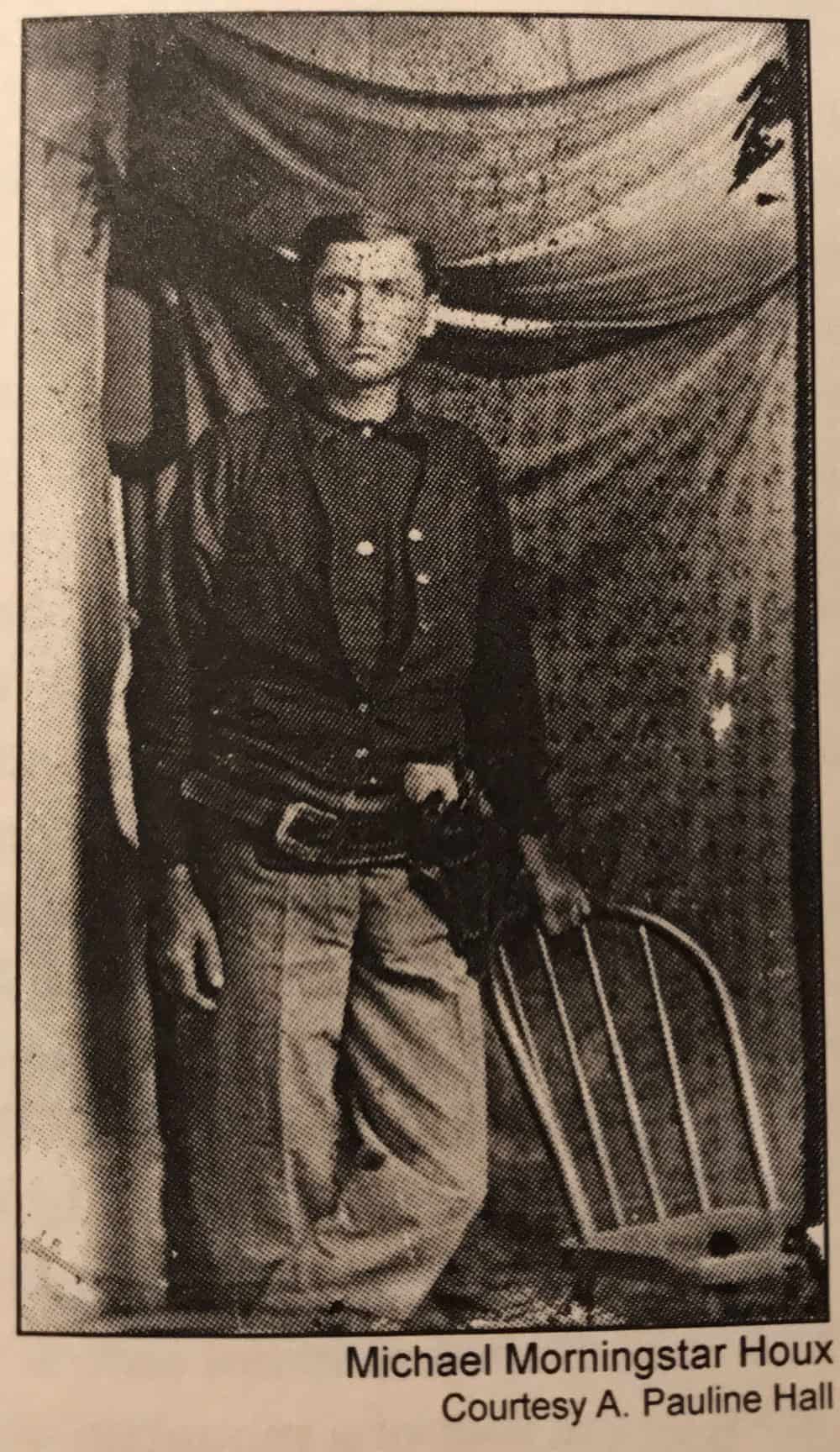

Michael Morningstar Houx. Photo from Houx family collection. Pictured here in Quantrill’s Thieves, by Joseph K Houts.

Also, I now knew why we were the way we were: generous, quick with a big genuine laugh, loyal. We’re also sarcastic, loud, and prone to an occasional family feud. You can take the Scots out of Ireland…

Because of this upbringing, I never DIDN’T know the name of my fourth great-grandfather Michael Morningstar Houx, the Confederate guerrilla who was on Quantrill’s original roster but left mid-war for Texas.

I never DIDN’T know that the beautiful old house on the hill belonged to his brother, Uncle Mat Houx and that he and a slave built it from walnut trees they felled clearing the land. (He also rode with Quantrill, faked his death once by putting his identifying information on a dead Federal soldier, escaped execution within hours of the scaffold, and gave the James brothers a place to hide when the Pinkertons were closing in. But I digress…).

I never DIDN’T know my fourth great-grandfather, Capt. Leroy Camden Duncan, who, being in law enforcement on the Missouri-Kansas border in the 1850s, made a valiant effort to appear neutral before the war but wound up commanding a company of Union men at a camp in Warrensburg in a spring-fed swampy depression with two small caves, providing cover and care to families of slaves making their way north to freedom. The house I grew up in was a block from there. Grandad Lee, “The Captain,” also provided the men with arms and transportation to Kansas if they wanted to fight.

And I never DIDN’T know that after the war he was assassinated for those heroic acts along with several others, one being his son, and his hometown of Kingsville sacked and burned by guerrillas (but not the Houxes, who were by now in Texas).

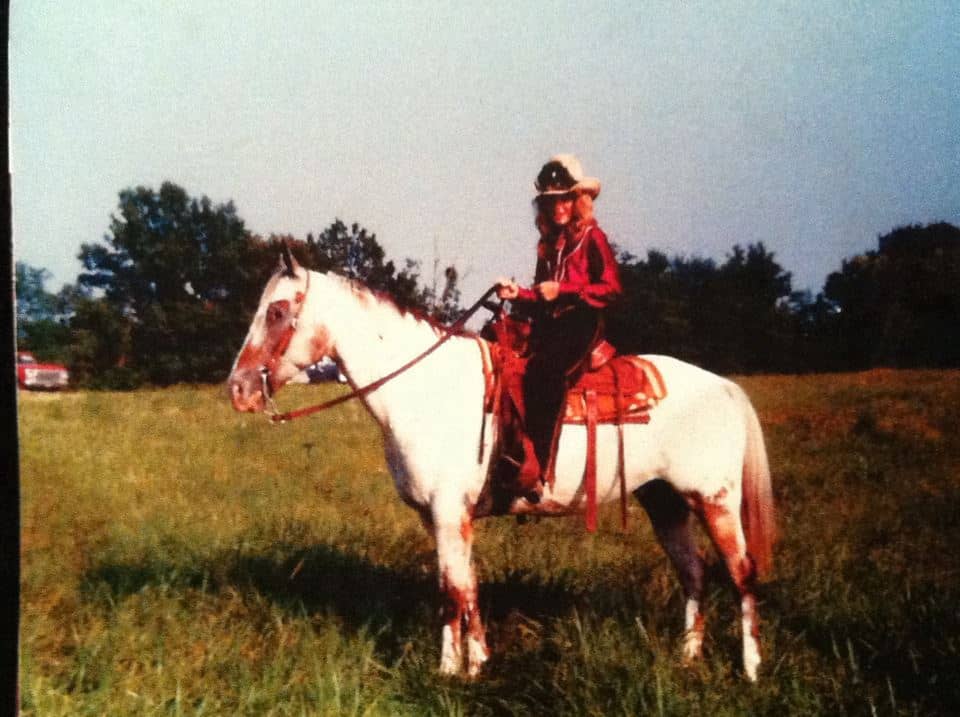

We talked about these people who lived 150 years ago like they were there, alive. I could feel them with me because I knew their stories, I rode my horses on the same land where they rode theirs. I have their pictures and documents that they wrote, held, read, and signed.

And out of all of this, something profound and unexpected happened when I lost my Dad rather suddenly in December.There is no filling the hole he left.

The void of that big ball of Type A energy that used to drive us nuts (“Would you just SIT DOWN?”). His innate and uncanny ability to sense a disturbance on the Force when one of us left anything of ours at his house when we left and we would get a call when we got to the end of the driveway. There was no “I’ll get it tomorrow.” You turned around or he’d bring it to you. His strength – from having to call him from the gas station for help because he put gas in your car last and you couldn’t get the gas cap off and had coasted up to the pump on fumes – to the way he shook hands like a man – a man that had worked so hard on the farm that the skin on his hands would come off. HARD work. The kind of work few people understand today because there were no weekends, no snow days, no sick days.

But I feel him. I feel him right there just like I feel Grandfather Michael, Uncle Mat, and Grandad Lee, and he’s there with them. He’s flying helicopters and jumping out of airplanes. He’s worshipping at the feet of Jesus. And he’s waiting for us.

I am so thankful for the way I grew up – not because it made the loss of my dad hurt less, because it didn’t. But it did bring an unexpected comfort and the feeling that it’s alright because I know I’m in a line for something much bigger. I know where I fit in and what those who came before me had to do in order for me to have the life I have now.

Because of their stories I know the meaning of true hard work and true sacrifice; those words are not cliché to me. I’m preparing a path, knowingly or unknowingly, for family 150 years in the future in just the same way they did for my family. I want to live a life with purpose even if unremarkable because I know my life will have an impact whether I’ve meant for it to or not.

I doubt my grandparents were thinking that’s what they were doing. They were just trying to keep their families safe, standing up for the rights of all people, or leaving their native country of Prussia with young children and a pregnant wife to find better lives in the Missouri Rhineland. My children and grandchild are hearing the stories, seeing the pictures and documents. They go with me to cemeteries and learn to respect the sacred ground and take care of the memorials, because each one represents the story of a life that made a difference to someone and this stone may be the only remaining record to tell us about them.

We will start our family reunions again because when all of the “stuff” life throws at us is stripped away, family is what matters. And sometimes our time with one of them is cut short. And when it is, we somehow find a way to get to the rest of the family to be there for them. We can’t make our only family reunions coincide with funerals.

8 Comments

Beautifully written Jodi!!! Don’t EVER lose this passion.

Oh Jodi! No wonder you want to go back to Missouri! Your heart is there, as is the lifeline of your memories! God bless you for conveying it so beautifully to the rest of us!

That’s beautiful Jodi. Makes me very proud to be your mom and a member of the family you’re writing about. You have a strong very proud heritage

Jodi, we’re so proud of you,what a wonderful story.love you u.b,a.d.

Loved this ♥️

Very nice article Jodi. I agree with you that our sense and understanding of where we come from, and who we came from, creates in us a drive to live meaningful lives, whether remarkable or not. You kind of feel like you owe it to your relatives of the past and those yet to come- all those with whom you share your lifeblood and name- to live, as you say, with purpose; to be somebody. Greatness may never be thrust upon you, or fame, but a simple life, well-grounded and well-lived, is honored in the memories of all those you’ve impacted; and maybe in that way your influence carries on. There will come a day when our graves will be looked after by those we’ve never met, who have to ask how many “Greats” to put in front of the word “Grand” when referring to us; who only know of us through old photos and stories. And hopefully, something in the telling of those stories will cause them to take a longer view of life and contemplate what kind of persons they ought to be, and what stories will be told of them. And they’ll want to bring honor to the name they read at the top of that gravestone, not because it’s their name, but because it was yours. Enjoyed the artical. Hopefully we’ll run into one another sometime.

Very nice article Jodi. I agree with you that our sense and understanding of where we come from, and who we came from, creates in us a drive to live meaningful lives, whether remarkable or not. You kind of feel like you owe it to your relatives of the past and those yet to come- all those with whom you share your lifeblood and name- to live, as you say, with purpose; to be somebody. Greatness may never be thrust upon you, or fame, but a simple life, well-grounded and well-lived, is honored in the memories of all those you’ve impacted; and maybe in that way your influence carries on. There will come a day when our graves will be looked after by those we’ve never met, who have to ask how many “Greats” to put in front of the word “Grand” when referring to us; who only know of us through old photos and stories. And hopefully, something in the telling of those stories will cause them to take a longer view of life and contemplate what kind of persons they ought to be, and what stories will be told of them. And they’ll want to bring honor to the name they read at the top of that gravestone, not because it’s their name, but because it was yours. Enjoyed the article. Hopefully we’ll run into one another sometime.

Very nice article Jodi. I agree with you that our knowledge of where we come from, and who we came from, creates in us a drive to live meaningful lives, whether remarkable or not. You kind of feel like you owe it to your relatives of the past and those yet to come- all those with whom you share your lifeblood and name- to live, as you say, with purpose; to be somebody. Greatness may never be thrust upon you, or fame- but there is immeasurable impact in a simple life- well-grounded and well-lived and preserved in the stories passed on to each generation. There will come a day when our graves will be looked after by those we’ve never met, who have to ask how many “Greats” to put in front of the word “Grand” when referring to us; who only know of us through old photos and stories. And hopefully, something in the telling of those stories will cause them to take a longer view of life and contemplate what kind of persons they ought to be, and what stories will be told of them. And they’ll want to bring honor to the name they read at the top of that gravestone, not because it’s their name, but because it was yours. Enjoyed the article. Hopefully we’ll run into one another sometime.